This article was originally posted here at Programmer’s Ranch with the title “C# WPF/MVVM: Why You Shouldn’t Bind PasswordBox Password”, on 4th October 2014.

Update 1st October 2018: As ZXeno posted in the comments, there seems to be a security flaw in the PasswordBox control by which it is possible to snoop passwords directly. The original premise of this article was that binding the password would expose it, but it turns out that it is already exposed regardless of whether you use data binding or not.

Hi! 🙂

In WPF circles, the PasswordBox control has generated quite a bit of discussion. The thing is that you can access the password entered by the user using the Password property, but it’s not a dependency property, and MVVM purists don’t like the fact that they can’t bind it to their ViewModel.

In this article, I’m going to show how the password can be bound in the ViewModel despite this limitation. And I’m also going to show you why it’s a very bad idea to do this. This article is a little advanced in nature, and assumes you’re familiar with WPF and MVVM.

Right, so let’s set up something we can work with. Create a new WPF application, and then add a new class called MainWindowViewModel. In your MainWindow‘s codebehind (i.e. MainWindow.xaml.cs), set up your window’s DataContext by adding the following line at the end of your constructor:

this.DataContext = new MainWindowViewModel();

Right, now let’s add a couple of properties to our MainWindowViewModel that we’ll want to bind to:

public string Username { get; set; }

public string Password { get; set; }

Now we can build our form by editing the XAML in MainWindow.xaml. Let’s go with this (just make sure the namespace matches what you have):

<Window x:Class="CsWpfMvvmPasswordBox.MainWindow"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

Title="Login"

Height="120"

Width="325">

<Grid>

<Grid.RowDefinitions>

<RowDefinition Height="20" />

<RowDefinition Height="20" />

<RowDefinition Height="30" />

</Grid.RowDefinitions>

<Grid.ColumnDefinitions>

<ColumnDefinition Width="90" />

<ColumnDefinition />

</Grid.ColumnDefinitions>

<TextBlock Text="Username:"

Grid.Row="0"

Grid.Column="0"

Margin="2" />

<TextBox Text="{Binding Path=Username}"

Grid.Row="0"

Grid.Column="1"

Margin="2" />

<TextBlock Text="Password:"

Grid.Row="1"

Grid.Column="0"

Margin="2" />

<PasswordBox Password="{Binding Path=Password}"

Grid.Row="1"

Grid.Column="1"

Margin="2" />

<Button Content="Login"

Grid.Row="2"

Grid.Column="1"

HorizontalAlignment="Right"

Width="100"

Margin="2" />

</Grid>

</Window>

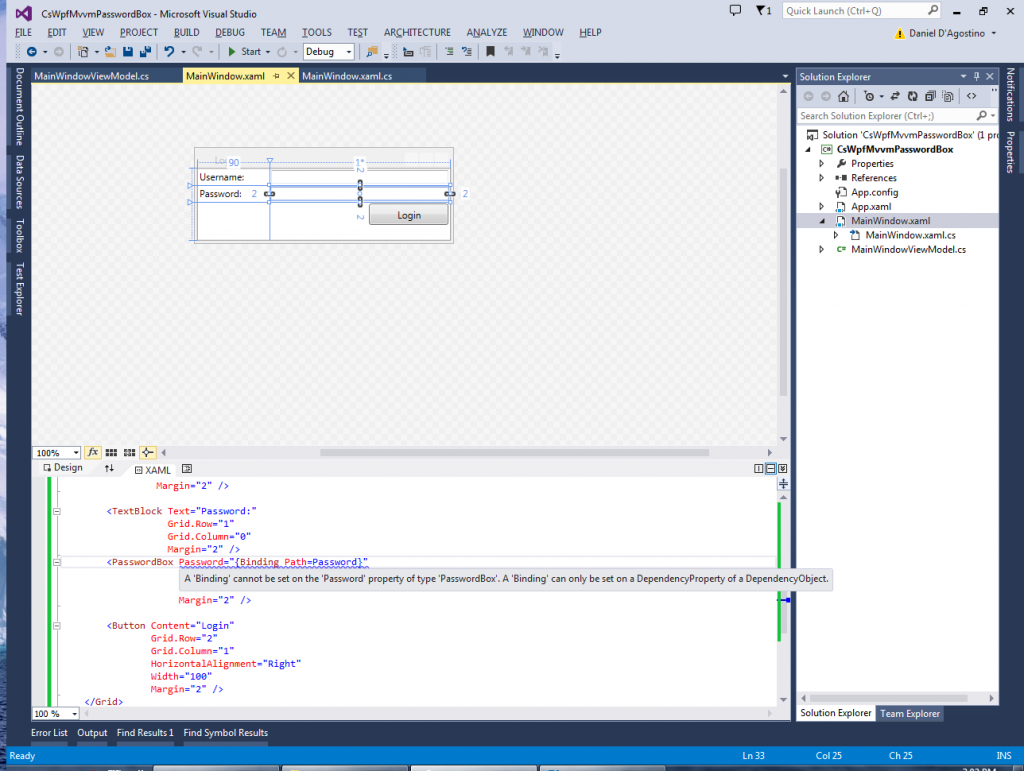

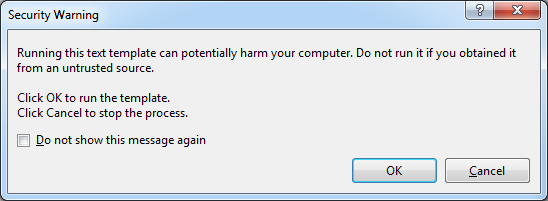

Now, you’ll notice right away that something’s wrong when you see the blue squiggly line at the password binding:

Oh no! What are we going to do now? If we can’t bind the password, and have to somehow retrieve it from the control, then we’ll break the MVVM pattern, right? And we MVVM knights-in-shining-armour can’t afford to deviate from the path of light that is MVVM. You see, the Password property can’t be bound specifically because it shouldn’t, but let’s say that we’re like most other developers and we’re so blinded by this MVVM dogma that we don’t care about the security concerns and we want an MVVM-friendly solution.

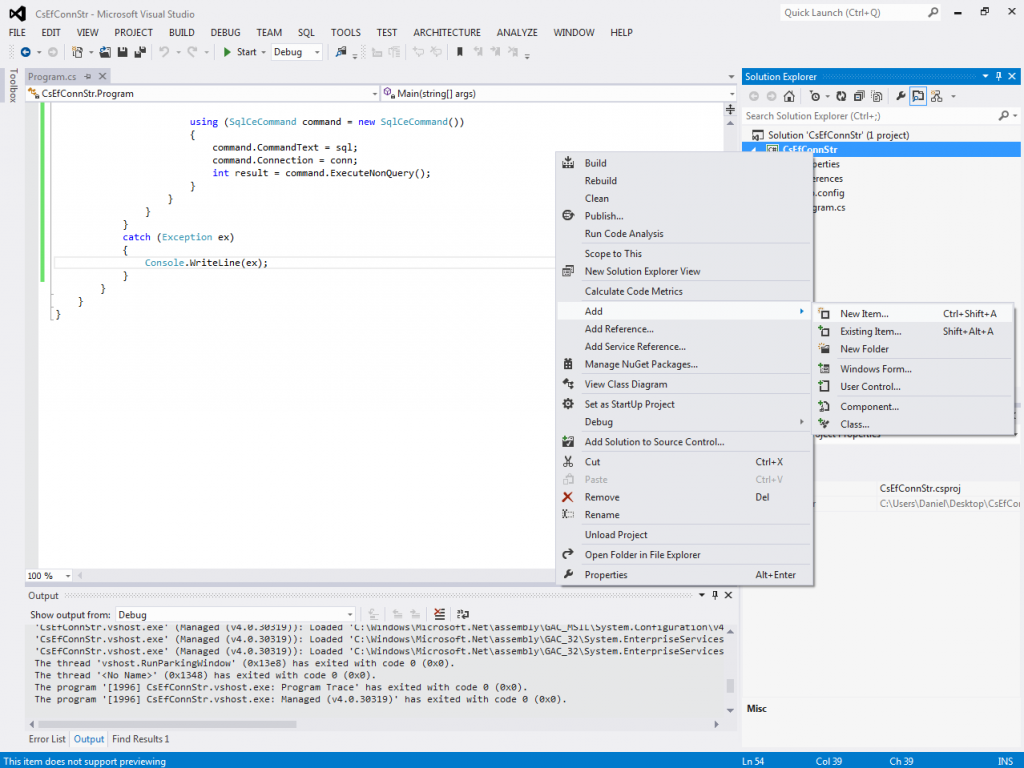

Well, no problem! It turns out that there actually is an MVVM-friendly way to bind the password – see the PasswordBoxAssistant and PasswordHelper implementations. To get up and running, let’s add a new PasswordBoxHelper class to our project, and add the implementation from the second link:

public static class PasswordHelper

{

public static readonly DependencyProperty PasswordProperty =

DependencyProperty.RegisterAttached("Password",

typeof(string), typeof(PasswordHelper),

new FrameworkPropertyMetadata(string.Empty, OnPasswordPropertyChanged));

public static readonly DependencyProperty AttachProperty =

DependencyProperty.RegisterAttached("Attach",

typeof(bool), typeof(PasswordHelper), new PropertyMetadata(false, Attach));

private static readonly DependencyProperty IsUpdatingProperty =

DependencyProperty.RegisterAttached("IsUpdating", typeof(bool),

typeof(PasswordHelper));

public static void SetAttach(DependencyObject dp, bool value)

{

dp.SetValue(AttachProperty, value);

}

public static bool GetAttach(DependencyObject dp)

{

return (bool)dp.GetValue(AttachProperty);

}

public static string GetPassword(DependencyObject dp)

{

return (string)dp.GetValue(PasswordProperty);

}

public static void SetPassword(DependencyObject dp, string value)

{

dp.SetValue(PasswordProperty, value);

}

private static bool GetIsUpdating(DependencyObject dp)

{

return (bool)dp.GetValue(IsUpdatingProperty);

}

private static void SetIsUpdating(DependencyObject dp, bool value)

{

dp.SetValue(IsUpdatingProperty, value);

}

private static void OnPasswordPropertyChanged(DependencyObject sender,

DependencyPropertyChangedEventArgs e)

{

PasswordBox passwordBox = sender as PasswordBox;

passwordBox.PasswordChanged -= PasswordChanged;

if (!(bool)GetIsUpdating(passwordBox))

{

passwordBox.Password = (string)e.NewValue;

}

passwordBox.PasswordChanged += PasswordChanged;

}

private static void Attach(DependencyObject sender,

DependencyPropertyChangedEventArgs e)

{

PasswordBox passwordBox = sender as PasswordBox;

if (passwordBox == null)

return;

if ((bool)e.OldValue)

{

passwordBox.PasswordChanged -= PasswordChanged;

}

if ((bool)e.NewValue)

{

passwordBox.PasswordChanged += PasswordChanged;

}

}

private static void PasswordChanged(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

PasswordBox passwordBox = sender as PasswordBox;

SetIsUpdating(passwordBox, true);

SetPassword(passwordBox, passwordBox.Password);

SetIsUpdating(passwordBox, false);

}

}

You will also need to add the following usings at the top:

using System.Windows; using System.Windows.Controls;

Now, let’s fix our Password binding. First, add the following attribute to the Window declaration in the XAML so that we can access our project’s classes (adjust namespace as needed):

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:CsWpfMvvmPasswordBox"

Then update the PasswordBox declaration to use the PasswordBoxHelper as follows:

<PasswordBox local:PasswordHelper.Attach="True"

local:PasswordHelper.Password="{Binding Path=Password}"

Grid.Row="1"

Grid.Column="1"

Margin="2" />

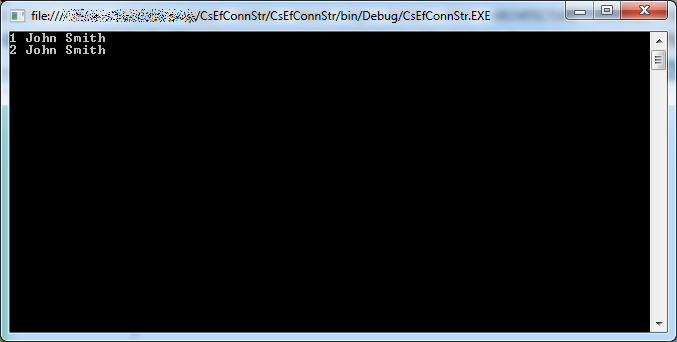

That did it! The project now compiles.

Now, let’s see why what we have done is a very stupid thing to do. To do this, we’re going to need this WPF utility called Snoop, so go over to their website, download it, and install it using the .msi file.

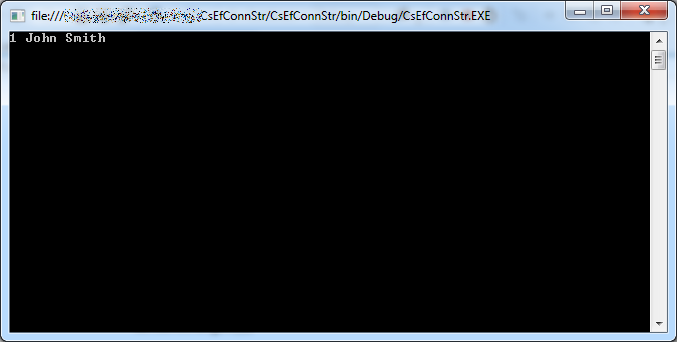

Run Snoop. All you’ll see is a thin bar with a few buttons. On the right hand side, there is a button that looks like a circle (in fact it’s supposed to be crosshairs). If you hover over it, it will explain how to use it:

Run the WPF application we just developed. Enter something into the PasswordBox, but shhhh! Don’t tell anyone what you wrote there! 🙂

Next, drag those crosshairs from Snoop onto the WPF window:

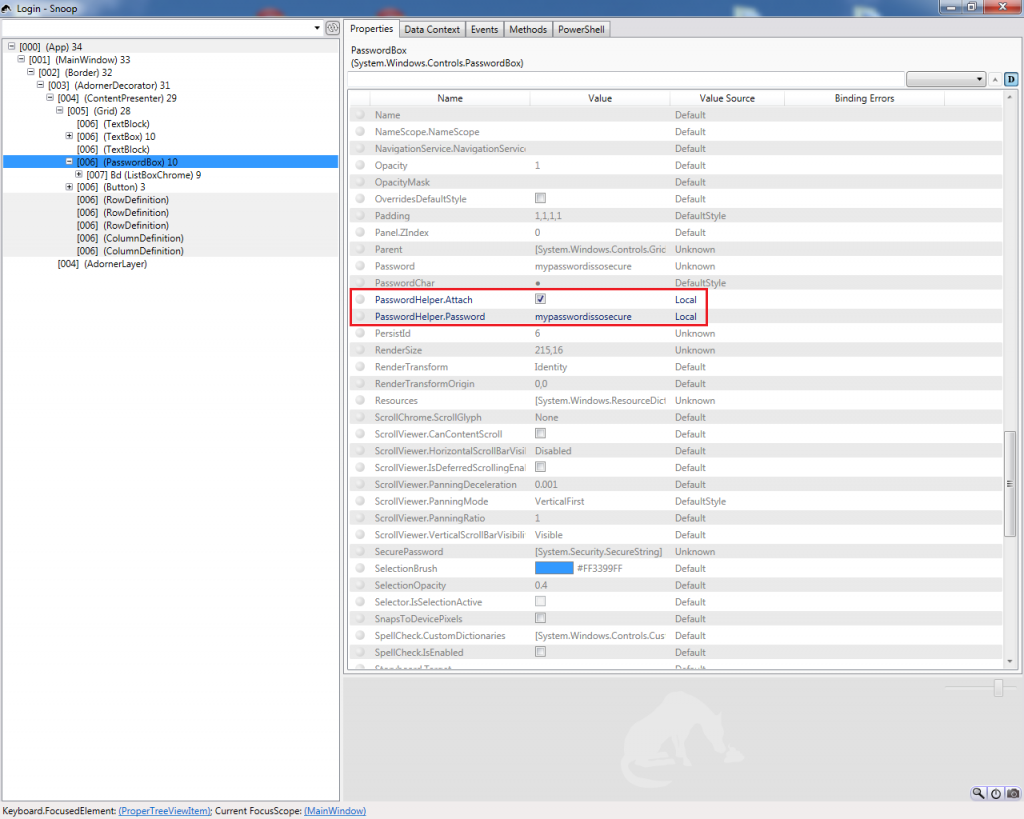

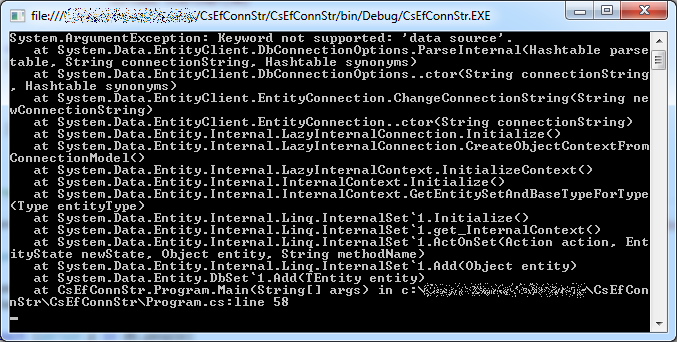

When you let go, a window opens. In the treeview to the left, you can navigate through the mounds of crap that internally make up our simple application. When you find the PasswordBox, you’ll also find the PasswordHelper:

…and as you can see, the PasswordHelper keeps the password exposed in memory so anyone who knows what he’s doing can gain access to it. With a program like Snoop, anyone can access passwords that are bound.

There are a couple of lessons to take from this.

First, don’t ever bind passwords in WPF. There are other alternatives you can use, such as passing your entire PasswordBox control as a binding parameter – although this sounds extremely stupid, it’s a lot more secure than binding passwords. And arguably, it doesn’t break the MVVM pattern.

Secondly, don’t be so religious about so-called best practices such as MVVM. Ultimately they are guidelines, and there are many cases such as this where there are more important things to consider (in this case, security). For something as simple as a login window, it’s much more practical to just do without MVVM and do everything in the codebehind. It isn’t going to affect the scalability, maintainability, robustness, [insert architectural buzz-word here], etc of your application if you make an exception that is rational.

Before ending this article, I would like to thank the person who posted this answer to one of my questions on Stack Overflow. That answer helped me understand the dangers of binding passwords, and provided the inspiration for this article. As further reading, you might also want to read this other question (and its answer) which deals with the security of processing passwords in memory in general (not just data binding).

That’s all for today. Happy coding! 🙂