This article was originally posted here at Programmer’s Ranch on 6th November 2013.

Hi guys and gals! 🙂

In this article, we’re going to see how to do XML serialization, which is really just a fancy way of saying we want to load and save objects as files in XML format.

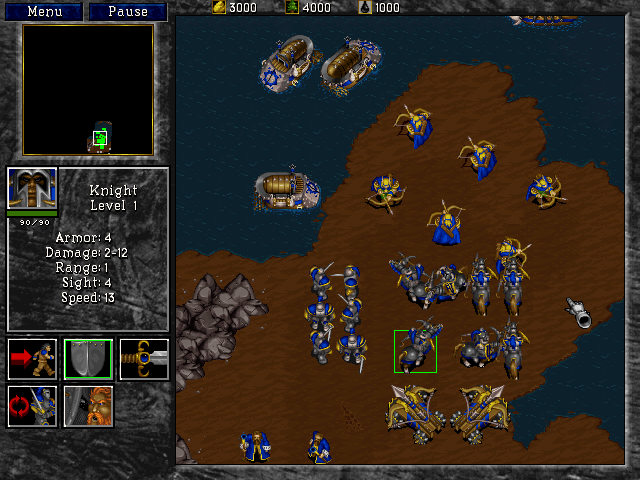

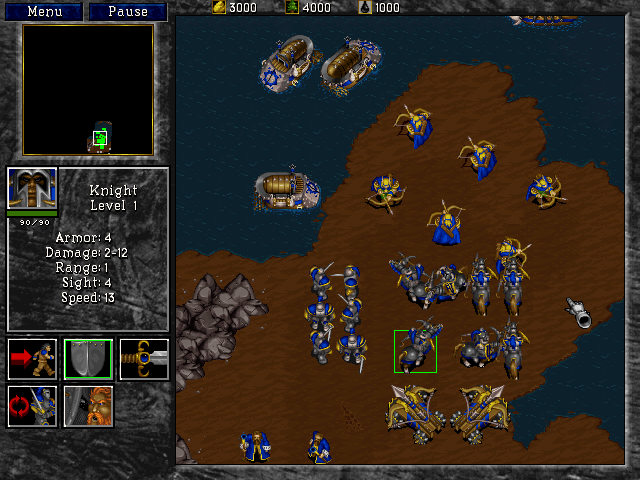

So you see, I’ve been a big fan of Warcraft 2 for a long time… probably about 15 years. In this game, you command different units (e.g. peasants, knights, etc), and each of them has different attributes such as Damage, Speed, etc. For instance, this is the mage:

Don’t mess with that guy – he can turn you into a sheep! And here’s the knight… not exactly a mild-mannered fellow, either:

If we represent those units and their attributes in XML, we might end up with something like this (I took out some of the extra crap that appears at the beginning when you actually save a file using XML serialization):

<UnitDatabase>

<units>

<Unit>

<Name>Mage</Name>

<Armor>0</Armor>

<MinDamage>5</MinDamage>

<MaxDamage>9</MaxDamage>

<Range>2</Range>

<Sight>9</Sight>

<Speed>8</Speed>

</Unit>

<Unit>

<Name>Knight</Name>

<Armor>4</Armor>

<MinDamage>2</MinDamage>

<MaxDamage>12</MaxDamage>

<Range>1</Range>

<Sight>4</Sight>

<Speed>13</Speed>

</Unit>

</units>

</UnitDatabase>

So, let’s see how we can actually read and write a file like this in C#. Create a new Console Application in your favourite IDE.

We first need to create a class to represent our units with their attributes. Create a class and call it Unit. For convenience, we can implement the attributes as auto-implemented properties as follows:

public String Name { get; set; }

public int Armor { get; set; }

public int MinDamage { get; set; }

public int MaxDamage { get; set; }

public int Range { get; set; }

public int Sight { get; set; }

public int Speed { get; set; }

This is just a quick alternative to declaring a member variable and a corresponding read-write property (available from .NET 3.0 onwards). For example, the Name property above is more or less equivalent to the following (just for demonstration – don’t actually add it to your code):

private String name;

public String Name

{

get

{

return this.name;

}

set

{

this.name = value;

}

}

Next, add a constructor to set the attributes, so we can easily create Unit instances from our main program code:

public Unit(String name, int armor, int minDamage, int maxDamage,

int range, int sight, int speed)

{

this.Name = name;

this.Armor = armor;

this.MinDamage = minDamage;

this.MaxDamage = maxDamage;

this.Range = range;

this.Sight = sight;

this.Speed = speed;

}

Now we need to create another class to hold an array of these units. Create a new class and call it UnitDatabase (admittedly a bit of a poor choice of a name, since it’s not actually a database, but anyway). Give it a Units property as follows:

public Unit[] Units { get; set; }

A constructor to assign this directly can also be pretty convenient. Add the following:

public UnitDatabase(Unit[] units)

{

this.Units = units;

}

Now we can implement our loading and saving code in UnitDatabase itself. Start by adding the code to save the UnitDatabase to a file:

public void Save(String filename)

{

XmlSerializer ser = new XmlSerializer(typeof(UnitDatabase));

using (StreamWriter sw = File.CreateText(filename))

ser.Serialize(sw, this);

}

You can see that we’re making use of the XmlSerializer class. The file is saved by using its Serialize() method, which takes a TextWriter and the object to serialize. The StreamWriter returned by File.CreateText() quite conveniently is a subclass of TextWriter, so we can pass it as the first parameter to Serialize(). The second parameter is this: the UnitDatabase itself.

To get this code to compile, you’ll have to add the following using statements at the top:

using System.Xml.Serialization;

using System.IO;

Loading an XML file as a UnitDatabase is just as easy. In this case we make the method static since it isn’t tied to any particular UnitDatabase instance:

public static UnitDatabase Load(String filename)

{

XmlSerializer ser = new XmlSerializer(typeof(UnitDatabase));

using (StreamReader sr = File.OpenText(filename))

return ser.Deserialize(sr) as UnitDatabase;

}

You can see that we’re still using the XmlSerializer, but this time we use the Deserialize() method to read the file from disk and create a UnitDatabase from it. Deserialize() takes a TextReader, which again is a base class of the StreamReader that we get by calling File.OpenText(), so everything fits like magic. Deserialize() returns an Object, so as a last touch we cast this to a UnitDatabase using the as keyword. It’s just the same as writing it like this:

return (UnitDatabase) ser.Deserialize(sr);

That’s all we need! Now, let’s add some functionality to make it easy to write our units to the console output. All classes inherit from Object, and Object defines this ToString() method which we can use to return a string representation of our objects. This is very convenient in our case, so we can implement Unit‘s ToString() method as follows:

public override string ToString()

{

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

sb.AppendFormat("Name: {0}", this.Name);

sb.AppendLine();

sb.AppendFormat("Armor: {0}", this.Armor);

sb.AppendLine();

sb.AppendFormat("MinDamage: {0}", this.MinDamage);

sb.AppendLine();

sb.AppendFormat("MaxDamage: {0}", this.MaxDamage);

sb.AppendLine();

sb.AppendFormat("Range: {0}", this.Range);

sb.AppendLine();

sb.AppendFormat("Sight: {0}", this.Sight);

sb.AppendLine();

sb.AppendFormat("Speed: {0}", this.Speed);

sb.AppendLine();

return sb.ToString();

}

Note the override keyword in the method’s signature. This means that we are replacing ToString()‘s default functionality (which usually just returns the name of the class) with our own, in this case showing the unit’s name and attributes.

Let’s do the same for UnitDatabase. In this case we return a concatenation of all the units’ string representations:

public override string ToString()

{

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

foreach (Unit unit in this.Units)

sb.AppendLine(unit.ToString());

return sb.ToString();

}

To compile this code, you’ll need to add the following line at the top of both files (because of the StringBuilder):

using System.Text;

Now all we have left to do is write code in Main() that actually uses these classes. We can start by creating our two units:

Unit mage = new Unit("Mage", 0, 5, 9, 2, 9, 8);

Unit knight = new Unit("Knight", 4, 2, 12, 1, 4, 13);

We can then combine these into an array using collection initializer syntax (see “C# Basics: Morse Code Converter Using Dictionaries” if you forgot what that is):

Unit[] units = new Unit[] { mage, knight };

Then, we create a UnitDatabase out of this array:

UnitDatabase db = new UnitDatabase(units);

…and finally save it to a file called units.xml:

db.Save("units.xml");

You can now press F5 to run the program and see that it works. If you’re using Visual Studio, you might have run into this error:

That’s because XML serialization needs classes to have an empty constructor. SharpDevelop creates one for you when you create a new class, but Visual Studio does not. So if you’re missing those, add them in. One for Unit:

public Unit()

{

}

…and one for UnitDatabase:

public UnitDatabase()

{

}

Good. Now press F5 to run the program, and then go to the project’s bin\Debug folder to check that the units.xml file has been created. When you open it, it should look like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<UnitDatabase xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema">

<Units>

<Unit>

<Name>Mage</Name>

<Armor>0</Armor>

<MinDamage>5</MinDamage>

<MaxDamage>9</MaxDamage>

<Range>2</Range>

<Sight>9</Sight>

<Speed>8</Speed>

</Unit>

<Unit>

<Name>Knight</Name>

<Armor>4</Armor>

<MinDamage>2</MinDamage>

<MaxDamage>12</MaxDamage>

<Range>1</Range>

<Sight>4</Sight>

<Speed>13</Speed>

</Unit>

</Units>

</UnitDatabase>

It’s got some more stuff in the first two lines than I showed you at the beginning, but that’s just added there to make it a valid XML document and you can just ignore it.

At the end of Main(), let us now add code to load the file and display the unit data:

UnitDatabase loadedDb = UnitDatabase.Load("units.xml");

Console.WriteLine(loadedDb.ToString());

Console.ReadLine();

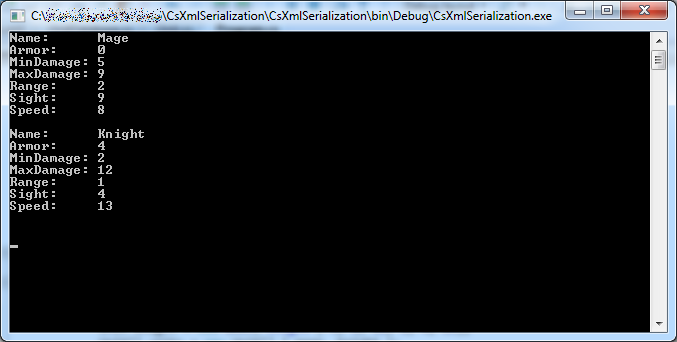

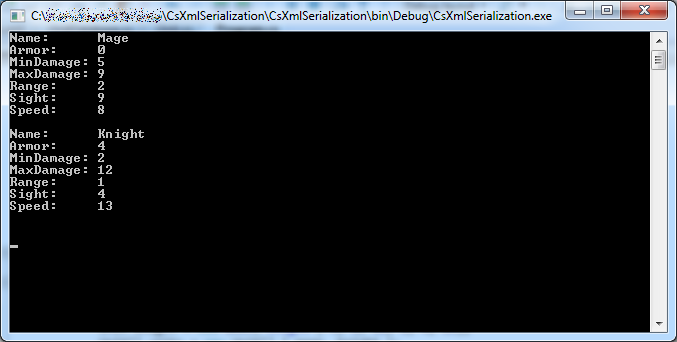

Press F5 to see the result:

If you omit the ToString() as follows:

Console.WriteLine(loadedDb);

…then the program works all the same, because Console.WriteLine() uses the ToString() method of the objects it is meant to write.

Great! 🙂 In this article, we have seen how we can very easily save (serialize) objects as XML files, and load (deserialize) them back from XML files. To do this we need classes that match the XML structure, as well as the handy XmlSerializer class. Classes to be serialized must have a parameterless constructor. It is possible to do a lot more with XML serialization – there are several attributes that allow you to control the actual XML nodes and attributes that are written to the file.

We have also seen other aspects of C#, such as the ToString() method available in every object; how to override inherited methods; the as keyword which is an elegant alias for type casting; and auto-implemented properties.

Thanks for reading, and come visit Programmer’s Ranch Gigi Labs again in future! 🙂